L. ALLOMORPHS

ALLOMORPHS: VARIATIONS OF MORPHEMES

DEFINITION:

An allomorph is ‘any of the different forms of a morpheme’. (Richards, Platt & Weber, 1987: 9)

EXAMPLE: long, length

MORPHEME FREE ALLOMORPH BOUND ALLOMORP {long} /lɔŋ/ /lεŋ-/

NOTE: a morpheme may have more than one phonemic form.

pt}

SELECTION OF ALLOMORPHS:

•The past-tense ending, the morpheme {-D pt}, has three phonemic forms.

1. After an alveolar stop /t/ or /d/, the allomorph /-ǝd/ takes place as in parted /partǝd/.

2. After a voiceless consonant other than /t/, the allomorph /-t/takes place as in laughed /lӕft/.

3. After a voiced consonant other than /d/, the allomorph /-d/ takes place as in begged /bεgd/.

•The occurrence of one or another of them depends on its phonological environment.

•This pattern of occurrence is called complementary distribution.

NOTE: These three phonemic forms of {-Dpt} are not interchangeable. They are positional variants. They are allomorphs belong to the same morpheme.

•It must be emphasized that many morphemes in English have only one phonemic form, that is, one allomorph – for example, the morpheme {boy} and {-hood} each has one allomorph - /bɔy/ and /-hUd/ - as in boyhood.

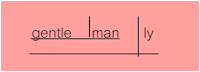

•It is really not the morpheme but the allomorph that is free or bound.

•For example the morpheme {louse} has two allomorphs: the free allomorph /laws/ as in the singular noun louse , and the bound allomorph /lawz-/ as in the adjective lousy.

1. ADDITIVE ALLOMORPHS:

To signify some difference in meaning, something is added to a word. For example, the past tense form of most English verbs is formed by adding the suffix –ed which can be pronounced as either /–t/, /–d/ or /–ǝd/:

ask + –ed = /ӕsk/ + /–t/, liv(e) + –ed =/lIv/ + /–d/, need + –ed =/nid/ + /–ǝd/.

2. REPLACIVE ALLOMORPHS:

To signify some difference in meaning, a sound is used to replace another sound in a word. For example, the /Ι/ in drink is replaced by the /æ/ in drank to signal the simple past. This is symbolized as follows:

/drænk/ = /drΙnk/ + / Ι > æ /.

3. SUPPLETIVE ALLOMORPHS:

To signify some difference in meaning, there is a complete change in the shape of a word.

For example:

_ go + the suppletive allomorph of {–D pt} = went;

_ be + the suppletive allomorph of {–S 3d} = is;

_ bad + the suppletive allomorph of {–ER cp} = worse;

_ good + the suppletive allomorph of {–EST sp} = best.

4. THE ZERO ALLOMORPH:

4. THE ZERO ALLOMORPH:

There is no change in the shape of a word though some difference in meaning is identified. For example, the past tense form of hurt is formed by adding the zero allomorph of {–D pt} to this word.

Source:

Stageberg, Norman C. and Dallin D. Oaks (2000). An Introductory English Grammar , Heinle, Boston:USA.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)